What is Setsubun ?

Setsubun (節分) is a traditional Japanese festival celebrated every year on February 3rd (or sometimes February 4th), marking the day before the start of spring according to the lunar calendar. The term Setsubun literally translates to “seasonal division,” symbolizing the shift between seasons, especially from winter to spring. While it is not a national holiday, Setsubun is widely observed throughout Japan with enjoyable, symbolic rituals meant to invite good fortune and drive away evil spirits.

Setsubun Origin

Setsubun dates back over a thousand years and is deeply rooted in Japan’s historical and religious practices surrounding seasonal changes, shinto purification rituals and buddhist concepts of protection and renewal. The festival’s roots are connected to ancient Chinese customs and Shinto beliefs, which emphasized the need to protect oneself from evil spirits and misfortune during times of seasonal transitions. Setsubun is tied to the Chinese lunar calendar, which was used in Japan until the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in the Meiji era (1868-1912). In ancient times, the changing of seasons, especially the shift from winter to spring, was seen as a vulnerable period when evil spirits were thought to be most active. The day before the first day of spring (known as Risshun), which falls on February 4th or 5th, marked the boundary between the old and new year.

Setsubun Traditions

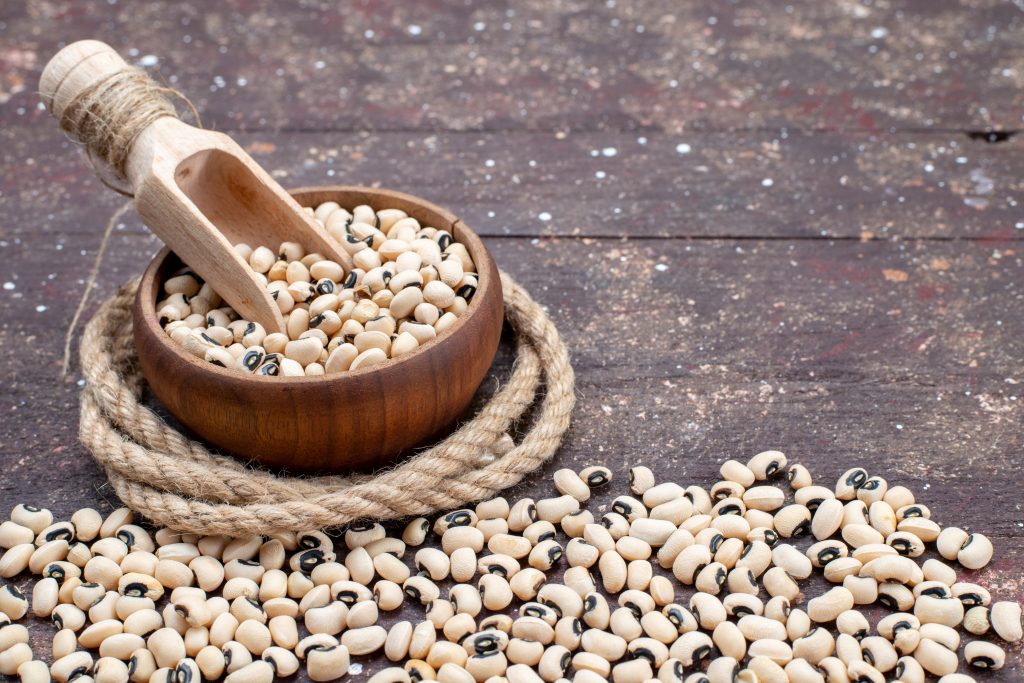

Mamemaki (豆撒き) – Bean Throwing :

The central tradition of Setsubun is the mamemaki or “bean throwing” ritual, which aims to drive away evil spirits (oni) and invite good fortune for the coming year. The term mame (豆), meaning “beans,” is also a homophone for mame (魔滅), meaning “to drive away demons.” During the ritual, people throw roasted soybeans inside or outside their homes while chanting “Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!” (鬼は外! 福は内!), meaning “Out with the demons! In with the good fortune!” This act is believed to purify the home and bring prosperity and health. In many households, a family member, often the father, dresses up as an oni (a demon or ogre), symbolically being driven away by the bean-throwing. The beans themselves represent purification and the defeat of misfortune.

Eho-maki (恵方巻き), or “fortune rolls” :

It is a relatively recent addition to Setsubun traditions. These special sushi rolls are eaten whole, without being cut into pieces, while facing the year’s lucky direction, known as eho (恵方). The lucky direction changes annually based on the Chinese zodiac, and eating the roll in silence while facing this direction is believed to bring good luck for the year. Eho-maki typically contains seven ingredients, such as pickled radish, cucumber, and fish, symbolizing the seven gods of good fortune (Shichifukujin).

Visiting Temples and Shrines:

During Setsubun, many people visit temples and shrines to participate in special ceremonies. Major temples like Senso-ji and Zojo-ji in Tokyo host large-scale mamemaki events, where monks, community leaders, and even celebrities throw beans to crowds of worshippers, who eagerly catch them for good luck. Some temples also provide setsubun beans for visitors to take home or offer as donations, continuing the tradition of purification and blessings.

Setsubun Today

While the festival’s roots in seasonal purification and exorcising evil spirits remain, modern Setsubun has become a more lighthearted, community-oriented event. People of all ages now participate. Setsubun is celebrated more widely in households than it was in the past, with even children participating in the ritual. The practice of eating eho-maki, in particular, has grown in popularity and is now a common feature of Setsubun celebrations in urban areas. Some people also throw fukumame (福豆) into the air at home to represent the scattering of good luck or place beans under their pillows at night for a peaceful, prosperous year.